A Guide to Pointers in Go

Let’s get real about pointers in Go—they’re not the scary beasts you might remember from C (if you came from that CS background). Go’s pointer implementation strikes that perfect balance between giving you low-level control and keeping you from shooting yourself in the foot.

For Python Developers: Why Care About Pointers? #

This blog introduces pointers, a fundamental programming concept many developers struggle with. Having worked with numerous senior Cloud Engineers, SREs, and Platform Engineers who, despite years of industry experience, have only Python knowledge and limited exposure to memory management concepts, I’ve crafted this primer to establish essential context before diving into the main teachings.

If you’re coming from Python, you might be wondering why we even need pointers. After all, Python handles everything behind the scenes, right? Well, that’s exactly the point - and also the limitation.

In Python, all variables are essentially references to objects. When you pass a variable to a function, you’re passing a reference, but you don’t get explicit control over whether something is passed by reference or by value. This is why you can modify a list inside a function, but not an integer.

Here’s an example:

# In Python, you can change mutable objects in functions

def add_cat(cat_list):

cat_list.append("Felix") # This modifies the original list

cats = ["Whiskers", "Mittens"]

add_cat(cats)

print(cats) # Output: ["Whiskers", "Mittens", "Felix"]

# But you can't change immutable objects

def age_cat(cat_age):

cat_age += 1 # This creates a new local variable

whiskers_age = 3

age_cat(whiskers_age)

print(whiskers_age) # Output: 3 (unchanged!)

Let’s visualize how Python’s implicit references differ from Go’s explicit pointers:

So What Are Pointers? #

Pointers are variables that store memory addresses. Instead of storing values directly, they point to where those values live in memory. This seemingly simple concept unlocks powerful programming patterns and performance optimizations.

Here’s what a pointer looks like in Go code:

var x int = 42

var p *int = &x // p is a pointer to x

The key symbols to understand:

&(address-of operator): Gets the memory address of a variable*(dereference operator): Gets the value stored at that memory address

Let’s visualize the core pointer concept:

How Go Manages Memory with Pointers #

Go’s memory model is worth understanding when working with pointers. Unlike C, Go features automatic garbage collection, which means you don’t need to manually free memory. This prevents many common pointer-related bugs.

Here’s a visualization of Go’s memory layout:

In Go:

- Stack: Fast memory for local variables (automatically cleaned up when function returns)

- Heap: Memory for objects that outlive their creating function

- Garbage Collector: Automatically cleans up unreachable objects in the heap

Setting Up a Go Project for Pointer Experimentation #

To follow along with the examples, create a small project structure:

mkdir pointers-demo

cd pointers-demo

go mod init pointers-demo

touch main.go

This creates a minimal Go module where you can experiment with the code examples that follow. We

will be editing and running main.go throughout.

go run main.goBasic Pointer Examples #

Let’s start with simple, practical examples of Go pointers in action.

Example 1: Working with Integer Pointers #

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Create an integer variable

count := 42

// Create a pointer to the integer

countPtr := &count

// Print the original value

fmt.Println("Original value:", count)

// Print the pointer (memory address)

fmt.Println("Pointer address:", countPtr)

// Dereference the pointer to get the value

fmt.Println("Dereferenced value:", *countPtr)

// Modify the value through the pointer

*countPtr = 100

// See that the original variable was changed

fmt.Println("New value:", count)

}

This example demonstrates the core operations of pointers:

- Creating a variable (

count) - Getting its memory address with

&(countPtr) - Accessing the value at that address with

*(*countPtr) - Modifying the original value through the pointer by assigning to

*countPtr

Let’s visualize what’s happening in memory:

Example 2: Working with String Pointers #

Pointers work with all types in Go, including strings:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Create a string variable

message := "Hello, Go!"

// Create a pointer to the string

messagePtr := &message

// Print original string

fmt.Println("Original:", message)

// Modify through pointer

*messagePtr = "Updated via pointer!"

// See the changed string

fmt.Println("Updated:", message)

}

When you run this code, you’ll see that modifying the string through the pointer affects the

original variable. This works because the pointer gives direct access to the memory where message

is stored.

The memory visualization:

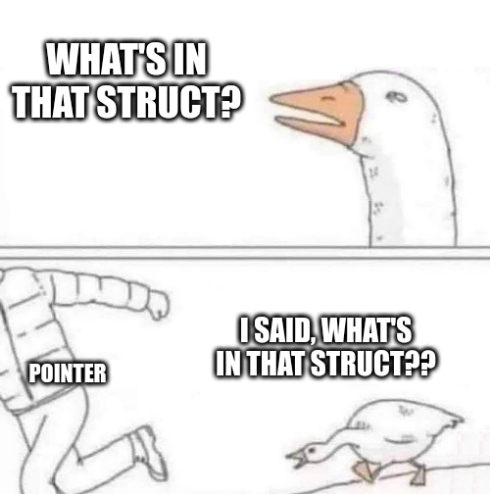

Example 3: Pointers to Structs #

Struct pointers are extremely common in Go for modifying complex data types:

package main

import "fmt"

// Define a simple struct

type Cat struct {

Name string

Age int

Breed string

}

func main() {

// Create a cat struct

whiskers := Cat{

Name: "Whiskers",

Age: 3,

Breed: "Maine Coon",

}

// Create a pointer to the struct

whiskersPtr := &whiskers

// Print original struct

fmt.Println("Original:", whiskers)

// Access and modify using pointer

// Go allows direct field access with struct pointers

whiskersPtr.Age = 4

// This is equivalent to (*whiskersPtr).Age = 4

// See the changed struct

fmt.Println("Updated:", whiskers)

}

Go provides syntax sugar for working with struct pointers. Notice that we can use whiskersPtr.Age

instead of needing to write (*whiskersPtr).Age. This convenience makes working with struct

pointers much more readable.

Let’s visualize the struct pointer:

Function Parameters and Pointers #

One of the most common uses of pointers in Go is to modify values within functions:

package main

import "fmt"

// This function modifies the cat via a pointer

func celebrateBirthday(c *Cat) {

c.Age++

fmt.Println("Happy Birthday, " + c.Name + "! You are now", c.Age)

}

type Cat struct {

Name string

Age int

Breed string

}

func main() {

mittens := Cat{

Name: "Mittens",

Age: 2,

Breed: "Tabby",

}

fmt.Println("Before:", mittens)

// Pass a pointer to the cat

celebrateBirthday(&mittens)

fmt.Println("After:", mittens)

}

Without pointers, Go is pass-by-value, meaning functions receive copies of arguments. By passing a

pointer, you’re enabling the function to modify the original value. The celebrateBirthday function

can directly modify the Person struct passed to it.

The function flow:

Nil Pointers and Safety #

Pointers in Go have a zero value of nil, which requires careful handling:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var ptr *int // Declared but not initialized

fmt.Println("Nil pointer:", ptr)

// Safety check before dereferencing

if ptr != nil {

fmt.Println("Value:", *ptr)

} else {

fmt.Println("Cannot dereference nil pointer!")

}

// Initialize the pointer

value := 42

ptr = &value

// Now safe to dereference

fmt.Println("Value after initialization:", *ptr)

}

Always check if a pointer is nil before dereferencing it. Attempting to dereference a nil

pointer will cause a runtime panic, which crashes your program.

Visualizing nil pointer safety:

Advanced Pointer Example: Custom Data Structure with Pointers #

Let’s build a simple linked list, one of the classic data structures that relies on pointers:

package main

import "fmt"

// CatNode represents a node in a linked list of cats

type CatNode struct {

Name string

Age int

Next *CatNode // Pointer to the next cat node

}

// CatList represents a linked list of cats

type CatList struct {

Head *CatNode

}

// AddCat adds a new cat node to the end of the list

func (l *CatList) AddCat(name string, age int) {

newCat := &CatNode{Name: name, Age: age}

if l.Head == nil {

l.Head = newCat

return

}

current := l.Head

for current.Next != nil {

current = current.Next

}

current.Next = newCat

}

// PrintCats prints all cats in the list

func (l *CatList) PrintCats() {

current := l.Head

for current != nil {

fmt.Printf("%s (age %d) -> ", current.Name, current.Age)

current = current.Next

}

fmt.Println("nil")

}

func main() {

// Create a new cat list

catList := CatList{}

// Add cat nodes

catList.AddCat("Whiskers", 3)

catList.AddCat("Mittens", 2)

catList.AddCat("Felix", 5)

// Print the list

catList.PrintCats() // Output: Whiskers (age 3) -> Mittens (age 2) -> Felix (age 5) -> nil

}

This example demonstrates how pointers enable the creation of a linked list data structure:

- Each

CatNodecontains cat information and a pointer to the next node - The

CatListhas a pointer to the head cat node - The

AddCatmethod traverses the list using pointers - The

PrintCatsmethod also traverses the list with pointers

Without pointers, implementing a linked list would be significantly more complex, if not im-paw-ssible.

When to Use Pointers in Go #

Here’s a decision guide for when pointers make the most sense:

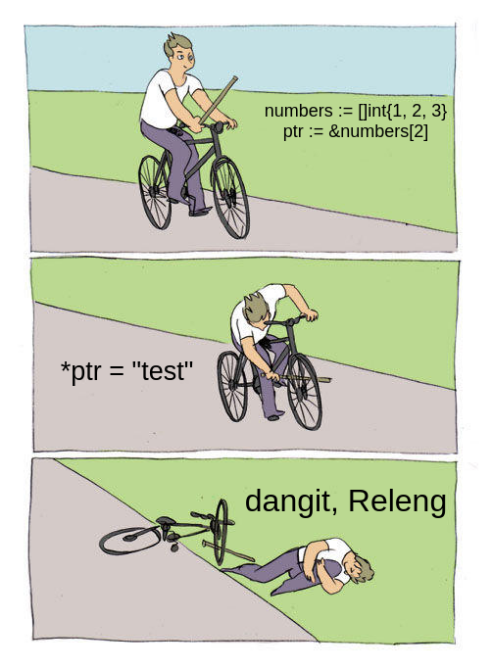

nil.Common Pitfalls with Pointers #

While Go’s pointers are safer than those in C/C++, there are still some common mistakes to avoid:

- Forgetting to check for nil: Always check if a pointer is

nilbefore dereferencing it. (I’m definitely guilty of failing to do this on projects) - Returning pointers to stack variables: Don’t return pointers to local variables, as they become invalid when the function returns.

- Unnecessary pointer usage: Using pointers for small, simple values can actually be less efficient due to indirection and garbage collection overhead.

- Pointer arithmetic: Go intentionally does not support pointer arithmetic to prevent buffer overflows and other memory corruption issues.

Wrapping Up #

Pointers in Go provide a powerful way to work with memory directly without the complexity and danger often associated with pointers in languages like C. They enable efficient memory usage and allow you to implement complex data structures like linked lists, trees, and graphs.

Key takeaways:

- Pointers store memory addresses, not values

- Use

&to get an address,*to get the value at an address - Pointers enable call-by-reference for modifying values in functions

- The zero value of a pointer is

nil - Always check for nil before dereferencing

- Pointers are crucial for implementing data structures like linked lists

By now, you should have a solid understanding of how pointers work in Go and be ready to use them in your projects. Start simple, experiment, and gradually incorporate these concepts into your Go programming toolkit.

Recommended Reading

Structs Fundamentals: From Basics to Advanced Usage

If you’ve been diving into Go programming (or “Golang” as the …

Understanding Go Interfaces

I still remember the moment it clicked. I was knee-deep in refactoring a Go CLI …

Go Channels: A Concurrency Guide

Hello fellow Gophers!

I’m absolutely thrilled to dive deep into one of …