Mastering DSAs in Go: The Big-O Guide [Part 1]

![Mastering DSAs in Go: The Big-O Guide [Part 1]](/images/gophers/go-grow.svg)

I’ve been really enjoying teaching fundamentals in Go, recently. If you haven’t read any of my other blogs or are new to go, I strongly recommend checking out my fundamentals posts. I started this blog as a next step, and before I knew it I was writing something way too long to share. This will be the first part of a blog series on data structures and algorithms; and of course, in Go!

In my opinion, understanding algorithm complexity is non-negotiable for writing efficient code. But let’s face it, you’re not always going to work on a team where engineers write efficient code (let alone an algorithm!). Even worse, you may work in a larger team with tech leads that don’t understand algorithms; resulting in your newer engineers missing out on the chance for proper mentorship in coding (or be taught bad practices!).

Big-O isn’t just academic theory—it’s a practical tool that determines whether your application will handle 10,000 users or crash when the 101st person logs in. Whether you’re new to Big-O or interested in learning it in Go, this blog will help teach you about these algorithms.

What is Big-O Notation? #

Big-O notation is how we describe an algorithm’s efficiency as input size grows. It’s like a speed limit sign for your code—telling you not how fast your algorithm runs on your M2 MacBook Pro, but how it will perform when your data grows from kilobytes to gigabytes.

In essence, Big-O focuses on the growth rate of time or space requirements as the input size increases toward infinity, ignoring constants and lower-order terms that become insignificant with large inputs.

Understanding Complexity Classes in Practice #

Let’s explore these complexity classes with practical Go implementations and see exactly what happens as our inputs grow.

O(1) - Constant Time: The Speed Champion #

Operations that execute in the same time regardless of input size. This is the gold standard we strive for.

// GetMapValue is an example of Constant Time

func GetMapValue(m map[string]int, key string) (int, bool) {

val, exists := m[key]

return val, exists

}

This function performs a hash table lookup which takes the same amount of time whether your map has 10 entries or 10 million. Go’s maps are implemented as hash tables, giving us O(1) average-case access time.

Here’s what happens behind the scenes:

The beauty of O(1) operations is their predictability—they’ll perform the same whether your app has 10 users or 10 million. This is why we love them for hot paths in our code.

O(log n) - Logarithmic Time: The Efficient Divider #

Algorithms that reduce the problem size by a fraction (typically half) with each step. The binary search is the poster child here.

// BinarySearch is an example of Logarithmic Time

func BinarySearch(sorted []int, target int) int {

left, right := 0, len(sorted)-1

for left <= right {

mid := left + (right-left)/2 // Avoids integer overflow

switch {

case sorted[mid] == target:

return mid // Found it!

case sorted[mid] < target:

left = mid + 1 // Look in the right half

case sorted[mid] > target:

right = mid - 1 // Look in the left half

}

}

return -1 // Target not found

}

Let’s trace through this with a concrete example:

sorted = [2, 5, 8, 12, 16, 23, 38, 56, 72, 91]

target = 23

- Initial state:

left=0, right=9, mid=4, sorted[mid]=16 - 16 < 23, so we set

left=5 - New state:

left=5, right=9, mid=7, sorted[mid]=56 - 56 > 23, so we set

right=6 - New state:

left=5, right=6, mid=5, sorted[mid]=23 - 23 == 23, return 5

With just 3 comparisons, we found our target in a list of 10 elements. If we had a million elements? It would take around 20 comparisons. That’s the power of O(log n).

The Go standard library uses binary search in

several places, like the sort.Search function. Here’s how you’d use it to find the position to

insert a new element while maintaining order:

import "sort"

func FindInsertPosition(sorted []int, value int) int {

return sort.Search(len(sorted), func(i int) bool {

return sorted[i] >= value

})

}

Remember that binary search requires sorted data, which is a crucial prerequisite. If your data isn’t sorted, you’ll need to sort it first (typically an O(n log n) operation), which changes the overall performance characteristics.

O(n) - Linear Time: The Honest Worker #

Operations where execution time grows in direct proportion to input size. Every element gets processed exactly once.

// ContainsElement is an example of Linear Time

func ContainsElement(slice []int, target int) bool {

for _, val := range slice {

if val == target {

return true

}

}

return false

}

This might look simple, but don’t underestimate it. Linear algorithms are often the best you can do for unsorted data, and they’re predictable and cache-friendly. The time required scales directly with the input size.

range is highly

optimized. The compiler can eliminate bounds checking in many situations, making linear scans

extremely efficient—sometimes approaching the theoretical memory bandwidth limit of your hardware.Linear algorithms are often unavoidable when you need to process all elements at least once, such as when calculating sums, finding maximum values, or checking if all elements meet a condition.

O(n log n) - Linearithmic Time: The Practical Sorter #

Found in efficient sorting algorithms and divide-and-conquer approaches, O(n log n) represents the best possible time complexity for comparison-based sorting.

Go’s standard library sort package implements an optimized version of quicksort (with insertion sort for small slices) that achieves O(n log n) average-case performance:

// QuickSort is an example of Linearithmic Time

func QuickSort(arr []int) []int {

// Make a copy to avoid modifying input

result := make([]int, len(arr))

copy(result, arr)

// Call the recursive helper

quickSortHelper(result, 0, len(result)-1)

return result

}

func quickSortHelper(arr []int, low, high int) {

if low < high {

// Partition the array and get the pivot index

pivotIndex := partition(arr, low, high)

// Recursively sort the sub-arrays

quickSortHelper(arr, low, pivotIndex-1)

quickSortHelper(arr, pivotIndex+1, high)

}

}

func partition(arr []int, low, high int) int {

// Choose the rightmost element as pivot

pivot := arr[high]

// Index of smaller element

i := low - 1

for j := low; j < high; j++ {

// If current element is smaller than the pivot

if arr[j] <= pivot {

// Increment index of smaller element

i++

arr[i], arr[j] = arr[j], arr[i]

}

}

// Swap the pivot element with the element at (i+1)

arr[i+1], arr[high] = arr[high], arr[i+1]

// Return the partition index

return i + 1

}

In this example, we used copy. If you are

not familiar with how this works, it accepts a destination slice type and a source slice type.

So in our use above, we copied all the values from arr into result. Without this copy step,

you’d be modifying the original slice that was passed in, which could lead to unexpected side

effects.

Now let’s analyze what happens during a quicksort with a small example:

arr = [38, 27, 43, 3, 9, 82, 10]

The recursive partitioning creates a tree-like structure of work:

In Go, prefer using the standard library’s sort

package for sorting needs rather than implementing your own. It’s well-optimized and handles edge

cases properly:

import "sort"

// For slices of basic types

nums := []int{5, 2, 6, 3, 1, 4}

sort.Ints(nums)

// For custom sorting

sort.Slice(people, func(i, j int) bool {

return people[i].Age < people[j].Age

})

The O(n log n) complexity comes from:

- The recursive partitioning creates a tree of height log n (divide)

- At each level, we do about n work comparing elements (conquer)

This makes it much more efficient than quadratic algorithms for large datasets. When sorting a million elements, quicksort would perform about 20 million operations compared to a trillion for bubble sort!

O(n²) - Quadratic Time: The Brute-Force Approach #

Characterized by nested loops, quadratic algorithms quickly become impractical as data size grows.

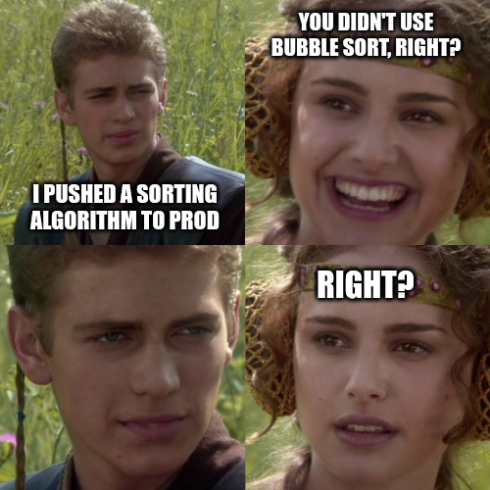

I once had an engineer message me on Slack, asking how I was able to retrieve a ton of data so fast. He asked if it was because I was using Go and because he was using Python. When I told him that was part of the reason, he said he was just going to use AI to rewrite it in Go; but before he went down the vibe coding route with his Cursor setup, I asked a bunch of leading questions about how he was processing the data. Turns out, he had vibe coded a very poor implementation of bubble sort (without understanding it)!

Let’s take a look at a cleaner implementation of bubble sort.

// Bubble Sort is an example of Quadratic Time

func BubbleSort(arr []int) {

n := len(arr)

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

swapped := false

for j := 0; j < n-i-1; j++ {

if arr[j] > arr[j+1] {

arr[j], arr[j+1] = arr[j+1], arr[j]

swapped = true

}

}

// If no swapping occurred in this pass, the array is sorted

if !swapped {

break

}

}

}

Bubble sort performs comparisons and swaps between adjacent elements, gradually “bubbling” the largest elements to their correct positions. Let’s walk through it:

arr = [5, 3, 8, 4, 2]

Pass 1:

Compare 5 & 3 → Swap → [3, 5, 8, 4, 2]

Compare 5 & 8 → No swap → [3, 5, 8, 4, 2]

Compare 8 & 4 → Swap → [3, 5, 4, 8, 2]

Compare 8 & 2 → Swap → [3, 5, 4, 2, 8]

Pass 2:

Compare 3 & 5 → No swap → [3, 5, 4, 2, 8]

Compare 5 & 4 → Swap → [3, 4, 5, 2, 8]

Compare 5 & 2 → Swap → [3, 4, 2, 5, 8]

Pass 3:

Compare 3 & 4 → No swap → [3, 4, 2, 5, 8]

Compare 4 & 2 → Swap → [3, 2, 4, 5, 8]

Pass 4:

Compare 3 & 2 → Swap → [2, 3, 4, 5, 8]

Final: [2, 3, 4, 5, 8]

Quadratic algorithms become impractical very quickly. For n = 1,000, a bubble sort performs nearly 500,000 comparisons. For n = 1,000,000, it would require about 500 billion comparisons! This is why we almost never use bubble sort in production code (or do we?).

Despite their inefficiency, quadratic algorithms sometimes appear in code bases:

- When processing small datasets where the simplicity of implementation outweighs performance concerns

- When the nested loops perform constant-time operations, making the code appear simpler

- In legacy code (languishing) that hasn’t been optimized

Always be suspicious of nested loops in performance-critical code paths, as they often indicate O(n²) complexity.

Practical Performance Comparison #

To drive home the dramatic differences between these complexity classes, let’s look at how they scale with input size:

| Input Size | O(1) | O(log n) | O(n) | O(n log n) | O(n²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 30 | 100 |

| 100 | 1 | 7 | 100 | 700 | 10,000 |

| 1,000 | 1 | 10 | 1,000 | 10,000 | 1,000,000 |

| 1,000,000 | 1 | 20 | 1,000,000 | 20,000,000 | 1,000,000,000,000 |

Notice how the O(n²) algorithm becomes completely impractical for large inputs, while O(log n) barely increases as the input size explodes. This is why binary search on a sorted array of 1 billion items still completes almost instantly, while a bubble sort would take years on the same data.

Go Standard Library Performance Tips #

The Go standard library was designed with performance in mind, and its implementations often use clever optimizations to achieve better-than-expected performance:

Go’s slice and map operations have specific performance characteristics you should know:

append()is amortized O(1) per element, though occasionally it requires O(n) work for resizing- Map iterations with

rangeare O(n) but in random order by design sort.Sort()uses introsort, a hybrid algorithm with O(n log n) complexitycopy()is O(n) where n is the minimum of the destination and source slice lengths

Beyond Big-O: The Devil in the Details #

While Big-O notation is crucial, it doesn’t tell the whole story:

- Constants matter: An O(n) algorithm with a high constant factor might be slower than an O(n log n) algorithm for practical input sizes

- Memory access patterns: Go’s slice operations are efficient partly because they leverage CPU cache locality

- Best/average/worst case: Some algorithms have different complexity in different scenarios

For example, Go’s map lookup is O(1) on average but could degrade to O(n) in the worst case with pathological hash collisions. In practice, this almost never happens due to Go’s implementation details.

When to Optimize? #

In Go, the general approach should be:

- Choose algorithms with appropriate complexity for your expected data scale

- Write clean, idiomatic Go code

- Profile to identify actual bottlenecks

- Optimize only where needed

Conclusion #

Understanding Big-O notation is a foundational skill for every Go developer. It helps you make informed decisions about algorithm selection and predict how your application will scale as data grows.

In the next part of this series, we’ll dive deeper into data structures and algorithms in Go!

Until then, remember: the difference between O(n) and O(n²) might be the difference between a system that scales smoothly and one that collapses under load.

References #

Recommended Reading

Mastering DSAs in Go - Data Structures [Part 2]

Hello, Gophers! Welcome to Part 2 of Data Structures and Algorithms. If …

Structs Fundamentals: From Basics to Advanced Usage

If you’ve been diving into Go programming (or “Golang” as the …

Modern Templating for Go with Templ

I’ve been working on a handful of personal webdev Go projects, and the one …